Engineering Illusions Part I: Religion and Technology — II

An Insider’s Take on the Tech Industry

Previous Installments:

Delusions of Godlike Grandeur

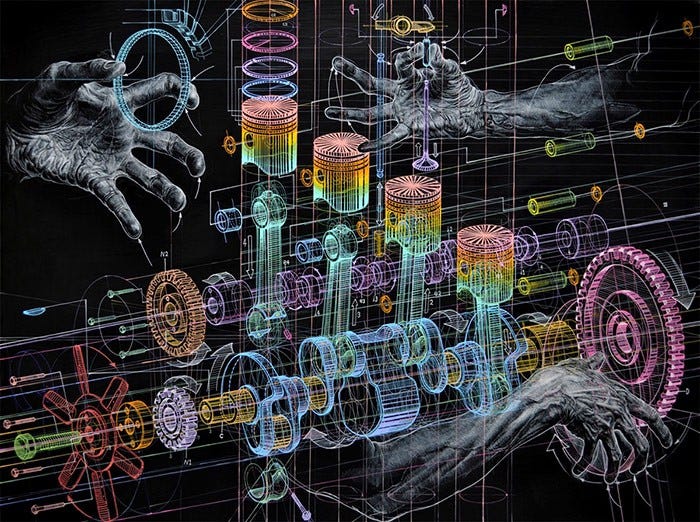

Centuries before the advent of SXSW and A.I sermons by tech CEOs, Descartes continued his investigations of mind-body duality. The prevalent ‘mechanical philosophy’ of the time led him to seek a complete understanding of the physical interactions between mind and body. The mechanical philosophy held that the world can be understood as a machine, built by the super-engineer in the heavens. Hence, its constitution was not unlike various mechanical machines and contraptions of the day. These machines were fully explainable, and there were no occult phenomena that controlled the devices. For instance, if a gear turned, it could be determined that a lever pushed on a shaft that turned the gear, and so on. The belief was that the world and all its physical phenomena could also be fully explained without evoking any mysterious forces. Two principle components in the world waiting to be understood and reconciled were mind and body. Galileo formulated the criteria for intelligibility as being able to “duplicate [all posits] by means of appropriate artificial devices.” It would be honoring God if the world was made fully intelligible.

However, with Newton’s discovery of gravitation, this philosophical edifice collapsed. As Newton showed, action at a distance governed the movements of the heavenly bodies; an occult, unintelligible force. As he described, action at a distance is “so great an absurdity, that I believe no man who has in philosophical matters a competent faculty of thinking, can ever fall into it.” The collapse of the mechanical philosophy would have reverberating effects till present day. Chomsky observed, “As the import of Newton’s discoveries was gradually assimilated in the sciences, the absurdity recognized by Newton and his great contemporaries became scientific common sense. The properties of the natural world are inconceivable to us, but that does not matter. The goals of scientific inquiry were implicitly restricted: from the kind of conceivability that was a criterion for true understanding in early modern science from Galileo through Newton and beyond, to something much more limited: intelligibility of theories about the world.” In other words, theories that formulated models of the world that had some predictive power were accepted as sufficient goals of natural philosophy.

Later developments such as Albert Einstein’s relativity and the quantum-mechanical revolution would only provide further theoretical constructions to model gravitation and action at a distance. It remains a mystery that has not only withstood the sandstorm of time, but it even reconfigured the goals of the scientific enterprise upon its discovery. As leading Enlightenment figure David Hume said of Newton, he was “the greatest and rarest genius that ever arose for the ornament and instruction of the species.” Through his brilliant discoveries, he “seemed to draw the veil from some of the mysteries of nature, he [showed] at the same time the imperfections of the mechanical philosophy; and thereby restored [nature’s] ultimate secrets to that obscurity, in which they ever did and ever will remain.” In essence, Newton lifted the veil, and revealed the veil.

Newton’s discovery further elevated the technical arts as a means to understand God. If our minds were incapable of conceiving grand celestial designs, perhaps our designs of various artifacts and devices would reveal God’s unfathomable intelligence to us. Paradoxically, Newton had always eschewed the technical arts. Natural philosopher and chemist Robert Boyle noted that Newton had always “displayed sovereign indifference to the practical usages of science,” and his lifelong dedication to understanding the governing principles of nature “directed almost exclusively to the knowledge of God.” Born on December the 25th, Newton’s deep religious convictions moved him “to search for divine efficacy in every aspect of the material order.” Indeed, understanding this concealed natural order through the application of the sciences would be to directly associate with the divine Creator. This was hardly a conviction unique to Newton. As Noble observed, virtually all seventeenth century English scientists believed in the approaching ascension at the millennium and regarded science as a means to approach divinity. It was this pursuit that led Newton to discover action at a distance, a phenomenon “so great an absurdity, that no man who has in philosophical matters a competent faculty of thinking, can ever fall into it.” It is then a matter of historical speculation to guess the fate of the pious program of technical salvation if the world was made wholly intelligible then.

It must be noted that with today’s rapid advancement of various techniques in A.I and machine learning, there is a trend that seeks to create predictive power not through conventional experimentation and modelling; rather, simply by crunching massive amounts of data to extract patterns for predictive purposes. It may not be far-fetched to think that as cloud services and inexpensive high-performance computers become more ubiquitous, we may see an acceleration in the ongoing migration towards utilizing various machine learning algorithms to estimate natural phenomena in various fields. This would constitute a second reduction in the goals of science, abandoning the already reduced goal of modelling the world through experimentation. Why bother studying weather systems and its various components if a neural net can be built to generate predictions based on a wide range of inputs? Why understand the mathematics behind astrophysical phenomena if large datasets can be searched for patterns and make projections of the next event? Ironically, these very tools that today promise to create the super-intelligent, Godlike mind seem to take us a step further away from the divine understanding that Galileo and Newton sought with devout practice. Never mind that, nor the possibilities of limits to our understanding. As a celebrity businessman bloviated, “At our current rate of technological growth, humanity is on a path to be godlike in its capabilities.”

Manifest Destiny: Divine Intelligence and Divine Life

In 1956, a pivotal Artificial Intelligence (A.I) conference was convened at Dartmouth. A groundbreaking event in A.I research, the conference brought together luminaries who would eventually go on to lead A.I programs at various research institutions. John McCarthy of MIT, the organizer, later established Stanford’s A.I program. Allen Newell and Herbert Simon led the A.I program at Carnegie-Mellon University. Marvin Minsky directed MIT’s A.I program. Also present among these architects was Claude Shannon, who along with English mathematician Alan Turing, developed the theoretical principles for the design of the electronic computer and its application to the study of A.I.

The development of “intelligent machines” was the unambiguous goal of the conference. According to the conference proposal, “the study [was] to proceed on the basis of the conjecture that every aspect of learning, or any other feature of intelligence, can in principle be so precisely described, that a machine can be made to simulate it.” As Minsky would later hypothesize in his 1961 paper Steps Towards Artificial Intelligence, advanced computing systems would make it “economical to match human beings in real time with really large machines.” These systems could yield machine-augmented “thinking aids” that could serve as a precursor to fully realized artificial intelligence. “In the years to come, we expect that these man-machine systems will share, and perhaps for a time be dominant, in our advance toward the development of artificial intelligence.” Repeating the same expectations when unveiling a brain-computer interface device in 2020, Elon Musk noted, “On a species level, it’s important to figure out how we coexist with advanced AI, achieving some AI symbiosis such that the future of world is controlled by the combined will of the people of the earth. That might be the most important thing that a device like this achieves.”

By the 1980s, the pursuit of A.I gave rise to the study of A.L, or Artificial Life. While A.I was the top-down attempt at recreating human intelligence to transfer to machines, A.L was a bottom-up pursuit to create the conditions within which the random, spontaneous generation of digital mathematical ‘life-forms’ could flourish. “Both approaches are needed for intelligent artificial life, and I predict that someday soon chaos theory, neural nets and fractal mathematics will provide a bridge between the two,” declared A.L pioneer Rudy Rucker in 1989. It was hypothesized that with sufficient time, intelligence would emerge, birthing pristine, super-intelligent mind-life. “Cellular automata will lead to intelligent artificial life. If all goes well, many of us will see live robot boppers on the moon.”

Noble observed, “Despite all their intellectual iconoclasm and futuristic fantasies, the A.L researchers remained mired in an essentially medieval milieu of Christian mythology.” Rucker declared, “I believe that science’s greatest task in the late twentieth century is to build living machines. In Cambridge, Los Alamos, Silicon Valley, and beyond, this is the computer scientist’s Great Work as surely as the building of the Notre Dame cathedral on the Ile de France was the Great Work of the medieval artisan.” He continued, “the manifest destiny of mankind is to pass the torch of life and intelligence on to the computer.” The religious fervor that deeply influenced A.L research was documented³ by Stanford anthropologist Stefan Helmreich, who observed during his stay at the Santa Fe Institute and Los Alamos, “Judeo-Christian stories of the creation and maintenance of the world haunted my informants’ discussions of why computers might be ‘worlds’ or ‘universes,’” alluding to elaborate speculations of living in a simulation. The researchers’ fascination included “stories from the Old and New Testaments (stories of creation and salvation).” This stitched the disciplines of A.I and A.L together with the common thread of religion. While the fulfillment of our “manifest destiny” to ascend from our fallen state to understand God’s unfathomable intelligence would rely on advancing A.I, that of understanding Creation and God’s design would rely on advancing A.L.

Today, the term A.I retains its original usage of super-intelligence. It is also commonly used to refer to the aforementioned narrow A.I applications. A 2016 New Yorker profile covered the journey of Sam Altman, a prominent Silicon Valley figure and former president of Y-Combinator (YC), a tech start-up incubator. Y-Combinator companies include Airbnb, Twitch, Doordash and Instacart. Author Tad Friend, referencing an experimental, computer-automated city that YC was conceptualizing, noted “You could imagine this metropolis as an exemplary post-human city-state, run on A.I. — a twenty-first-century Athens — or as a gated community for the élite, a fortress against the coming chaos. For Altman, the best way to discover which future was in store was to make it.”

The piece’s fortuitous title? Sam Altman’s Manifest Destiny.

Technological Transcendence

In the ninth century, Carolingian philosopher and theologian Johannes Scotus Erigena was the first to propound the august nature of the useful arts as a means of salvation. Sufficient intellectual deliberation and cultural infusion led to the stamping of the term ‘mechanical arts,’ referring to the collection of applied techniques to achieve various practical ends. Mechanical arts would later be replaced by terms such as ‘useful arts’ and ‘technology.’ Erigena’s formulations led to a “boldly innovative and spiritually promising reconceptualization of the arts” that “signaled a turning point in the ideological history of technology,” noted Noble. As Pope John Paul II would repeat much later in 1981, “Science and technology are wonderful products of a God-given human creativity.”

The innovation here was the proposition that the capacity for the arts was innate to human nature. As Erigena argued, the arts are “man’s links with the Divine, their cultivation a means of salvation.” Since “every natural art is found materially in human nature,” “it follows that all men by nature possess natural arts, but, because, on account of the punishment for the sin of the first man, they are obscured in the souls of men and are sunk in a profound ignorance, in teaching we do nothing but recall to our present understanding the same acts which are stored deep in our memory.”⁴ Noting this conception of the arts as an innately divine pursuit, historian Elspeth Whitney wrote, “It would be difficult to overestimate the significance of this development. The new emphasis on the place of the arts in Christian education must be seen as one of the chief factors animating the ninth century’s intense interest in the arts.”⁵ Such a novel Christianization of the mechanical arts for “the first time gave the means of mortal survival a crucial role in the realization of immortal salvation,” noted Noble.

Gradually, this amalgamation hardened in the seventeenth century, when “a literal reading of the Bible, in particular the prophetic books of the Old Testament and the Book of Revelation of the New Testament, became central to all arts, sciences and literature.” The technical arts continued to draw purpose from religion. In a milieu obsessed with scripture, speculations about heavenly ascension and the end times charged the cultural consciousness. The mechanical arts provided routine sparks. Prevalent philosophical doctrines, inseparable from theological speculations, only added to the zeal. “And herein the monastic and millenarian conceptions of redemption, which had ideologically ignited the advance of the arts, crystallized as never before: the monastic idea of transcendence as a recovery of mankind’s divine likeness, a restoration of Adamic perfection, knowledge, and dominion, a return to Eden, and the identification of the arts as a vehicle of such transcendence.”

The promise of emancipation expressed in Daniel 12:4 — “But you, Daniel, shut up the words, and seal the book until the time of the end; many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall increase”- was potent prophecy that elevated the scientific and technical arts to the pursuit of the divine. Historian Richard Popkin observed, those of the age “took seriously the injunction in Daniel that, as the end approaches, knowledge and understanding will increase, the wise will understand, while the wicked will not. They also took seriously the need to prepare, through reform, for the glorious days ahead. Their efforts to gain and encourage scientific knowledge, to build a new educational system, to transform political society, were all part of their millenarian reading of events. They needed to understand, to construct a new theory of knowledge, a new metaphysics, for the new situation, the thousand-year reign of Christ on Earth, which was to be followed by a new heaven and a new earth.”⁶

Similarly, John 14:12 — “Verily, verily I say unto you, he that believeth in Me, the works that I do he shall do also; and greater works than these shall he do, because I go unto My Father.” — provided a divine dictum to direct the technical arts for the construction of nirvana.

Noble observed that “this unprecedented millenarian milieu decisively and indelibly shaped the dynamic Western conception of technology. It encouraged a new lordly attitude towards nature.” Studying the period, historian Charles Webster wrote, “the technological discoveries of the Renaissance, particularly those relating to gunpowder, printing [both invented in China] and navigation appeared to represent a movement towards the return of man’s dominion over nature.” Enflamed with visions of New Jerusalem under the anticipation of the approaching thousand year age, poet John Milton declared that man’s triumph would be marked by nature’s “surrender to man as its appointed governor, and his rule would extend from command of the earth and seas to dominion over the stars.”⁷

Francis Bacon, King James’s Lord Chancellor, was the preeminent voice among the reformers in the seventeenth century. Among Puritans, Bacon’s “writings came to attain almost scriptural authority,” observed Webster. Few figures were more influential in the religious project of technology; or more accurately, the technical project of religion. Aroused by the oncoming ascension, the religious thinkers of the day developed reforms for the millenarian implementation of the mechanical arts. This “utopian endeavor” was guided by Bacon’s Instauratio Magna, a comprehensive plan to reorganize the scientific and technical enterprise to restore man’s lordship over nature, and his rightful place of divinity thought to be lost by the fall of Adam. “For Bacon, the sustained development of the useful arts offered the greatest evidence, and the best means, of millenarian advance,” noted Noble. Ascension was imminent. As the scholarly and knowledgeable men of the age insisted, the millennium was at hand. These technologies shall reclaim for humanity its lost perfection.

The Perfect Cell

Few fields better encapsulate in their history and practice the search for divine perfection than biotechnology. Early efforts in the study of life first strove to understand the mechanisms of life and conceive of techniques and machines that would improve the activities of living beings. The early pious practitioners of these arts sought to study and then recast life itself — hence, in the deed, honoring the creations of God. American author Edward Bellamy wrote in his nineteenth century utopian work Looking Backward, “The betterment of mankind from generation to generation, physically, mentally, morally, is recognized as the one great object supremely worthy of effort and of sacrifice. We believe the race for the first time to have entered on the realization of God’s ideal of it, and each generation must now be a step upward.”

Contemplating on the end of life, and insisting on humankind’s spiritual duty to decode the secrets of life during its brief mortal existence, he noted, “For twofold is the return of man to God ‘who is our home,’ the return of the individual by the way of death, and the return of the race by the fulfillment of the evolution, when the divine secret hidden in the germ shall be perfectly unfolded. With a tear for the dark past, turn we then to the dazzling future, and, veiling our eyes, press forward. The long and weary winter of the race is ended. Its summer has begun. Humanity has burst the chrysalis. The heavens are before it.” Unlocking these “secrets hidden in the germ” would make accessible God’s divine designs. The goal of decoding life would later evolve into one of engineering life. Complex systems scientist J. Doyne Farmer would observe a century later, “When we acquire the ability to interpret the messages of the genome, we will be able to design living things.”

Attaining the means of controlling nature became a part of reasserting humankind’s dominance over the natural world. This would fulfill its consecrated role in the process of creation. The conquest of nature wouldn’t simply be limited to other life forms. That would be a stunningly anemic display of ambition. Indeed, the zenith of the conquest resided in our own form. “Turning their newfound powers upon their own kind, they would seek finally to purify the human species of the physical frailties with which it had been cursed, thereby to restore it to its original perfection,” noted Noble.

The field’s trajectory towards this conclusion had been set since its primitive conception. During its early stages, the pilot flames for the desire to create life had already been lit. “Hermetic philosophers and alchemists had long dreamed of uncovering the secret of life and learning how to create life themselves, typically by means of esoteric incantations or incubations of life-giving menstruum.” Just as God had infused Adam’s earthly matter with life, the storied Rabbi Low of Prague “breathed the name of God into a clay figure to create his celebrated golem.” Aforementioned A.I pioneer Marvin Minsky believed himself to be a direct descendant of Rabbi Low.

Prior to the collapse of the mechanical philosophy, Descartes had proposed that the world could indeed be reduced to a collection of machines. This applied to all living creatures as well. As John Cohen noted, Descartes “proposed that the bodies of animals be regarded as nothing more than complex machines. Caution restrained him from saying as much of man himself, but he went as far as he dared without imperiling his life.”⁸ With this conception, Descartes was one of the first to expand mechanical analysis into the subject of natural biology. Francis Bacon concurred in his idealistic visions of the famous New Atlantis — a seventeenth century novel that depicts the scientific leaders of Solomon’s House establishing their preordained rule over nature in search for perfection. “The curing of diseases counted incurable,” “the prolongation of life,” “the retardation of age,” the “transplanting of one species into another,” the “making of new species,” and the development of “instruments of destruction, as of war and poison,” as Bacon proposed, were all accessible feats once the mechanisms of life were understood.

Bacon had imagined in New Atlantis man-made species through the combination of various traits of different creatures. This would, in Bacon’s mind, “demonstrate not only the restoration of mankind’s rightful dominion over all other creatures but also its God-like participation in the process of creation itself,” Noble observed. With advanced genetic engineering technologies, molecular biologists would eventually realize capacities far beyond Bacon’s wildest fantasies. Mere cross-breeding would hardly mark the pinnacle of the field, one that would later hold as its crowning exploit the precise modification and enhancement of life at the genetic level.

Such grand powers would have to remain latent till the discovery of the DNA molecule. In the mid-1950s, X-ray crystallography played a major role in the study of the structure and function of DNA. Irish life scientist and X-ray crystallography pioneer J.D Bernal wrote in The World, the Flesh and the Devil: An Enquiry into the Future of the Three Enemies of the Rational Soul, “Normal man is an evolutionary dead end; mechanical man, apparently a break in organic evolution, is actually more in the true tradition of a further evolution.” Predicting the replacement of natural biology by enhanced biology, Bernal declared, “Bit by bit the heritage in the direct line of mankind — the heritage of the original life emerging on the face of the world — would dwindle, and in the end disappear effectively, being preserved perhaps as some curious relic, while the new life which conserves none of the substance and all of the spirit of the old would take its place and continue its development. Such a change would be as important as that in which life first appeared on Earth’s surface.” Per Bernal, the application of the sciences would actively guide the processes of Creation. Upon the discovery of the double-helix structure of the DNA molecule, the English physicist Francis Crick declared, “We have discovered the secret of life.” Nucleic-acid chemist Erwin Chargaff designated the double helix as “the mighty symbol that has replaced the cross as the signature of the biological analphabet.”⁹ Noble noted, “This view of DNA as an eternal and hence sacred life-defining substance — indeed, the new material basis for the immortality and resurrection of the soul — became a modern article of faith. DNA spelled God, and the scientists’ knowledge of DNA was a mark of their divinity.”

Once the structure of the DNA was understood, the far more challenging task of understanding its function and operation began. The physical container of genetic information that dictates the generation of new life material, the DNA molecule’s structure embeds within it instructions for replication. Contained within DNA is the code that creates the building blocks of life — proteins. This discovery again opened the possibility of understanding life through a mechanistic view. “If the advocates of artificial intelligence viewed machine as potentially lifelike, the molecular biologists viewed life as essentially machine-like,” observed Noble.

Years before this discovery, Bernal had prophesied that to simply understand or even make life would be an insufficient endeavor for scientists; rather, to augment it would be the final objective. Indeed, as the fields advanced, a formalized enterprise emerged to realize that ambition. As the science and associated technologies matured, the study of biology turned its gaze towards the modification of life. These biotechnologies enabled humankind to impose its Godly will over plebeian nature to modify lower organisms per its own needs. Most importantly, however, it endowed God’s favorite children with capacities to modify their own form.

Genetic experiments moved on to humans over time, and the advent of human gene therapy sought genetic cures to various diseases. Any characteristic that prevented the attainment of Adamic perfection began to be understood as diseases as well. One such trait was intelligence, deemed to be occurring undesirably randomly in the human population. As Bernal wrote, there was an unfortunate and undesirable need to recruit the “aristocracy of scientific intelligence” from the masses of ordinary people, a process that relied on “the diffusion of a general education.” Such a random process could be replaced with a deterministic one once “we can know from the inspection of an infant or an ovum that it will develop into a genius.”

As the “aristocracy” then surmised, the genes could hold the key to eugenic modifications by making genetic improvements within the present population and future generations. Warren Weaver, the director of natural sciences at the Rockefeller Foundation, had asked in 1934, “Can we obtain enough knowledge of the physiology and psychobiology of sex so that man can bring this aspect of his life under rational control? Can we unravel the tangled problem of the endocrine glands and develop a therapy for the hideous range of mental and physical disorders which result from glandular disturbance? Can we develop so sound and extensive a genetics that we can hope to breed, in the future, superior men? Can we solve the mysteries of the various vitamines [sic], so that we can nurture a race sufficiently healthy and resistant? Can psychology be shaped into a tool effective for man’s everyday use? In short, can we rationalize human behavior and create a new science of man?”¹⁰

In 1969, molecular geneticist Robert Sinsheimer echoed congruent sentiments, declaring, “It is a new horizon in the history of man. Some of you may smile and may feel that this is but a new version of the old dream, of the perfection of man. It is that, but it is something more. The old dreams of the cultural perfection of man were always sharply constrained by his inherent, inherited imperfections and limitations. Man is all too clearly an imperfect, a flawed creature. And to foster his better traits and to curb his worse by cultural means alone has always been, while clearly not impossible, in many instances most difficult. It has been an Archimedean attempt to move the world but with the short arm of the lever. We now glimpse another route — the chance to ease the internal strains and heal the internal flaws directly — to carry on and consciously to perfect, far beyond our present vision, this remarkable product of two billion years of evolution.” Later in 1990, the National Institutes of Health would award a significant grant to geneticist Robert Plomin to identify genes for IQ that characterized what he called “the really smart kids.”

Next: Religion of Technology — III

Follow along on Twitter @ap_prose and Medium at Tech Insider for the next installment of Engineering Illusions!

Sources:

3. S. Helmreich, Anthropology Inside, MIT Anthropology

4. A. Guiu, A Companion to John Scottus Erigena, pg 56

5. E. Whitney, Paradise Restored, pg 26, pg 70–72

6. R. Popkin, Millenarianism and Messianism in English Literature and Thought

7. C. Webster, Great Instauration

8. J. Cohen, Human Robots in Myth and Science

9. E. Chargaff, Heraclitean Fire

10. Nicolas Rasmussen, Picture Control, pg 9